“What’s this place?”

That is the first line of dialogue spoken in Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” and is a question that resonates throughout much of the film. In the opening moment, Han Ye-Ri speaks as Monica – the matriarch of the four-person nuclear family. Her husband, Jacob, has moved the family from California to a plot of land in rural Arkansas. The move does not come without problems, and the first leads to that opening question. As Emile Mosseri’s disturbing score plays out, the family drives to their new home. They step out of the vehicles and consider the home in front of them: A mobile home, surrounded by vacant land that Jacob will turn into a farm. This is not what Monica was expecting.

In the moment, we watch Han contemplate the house in front of her. She raises her hands to her eye, as protection from the sun, but also as if to give her a moment to shut down her feelings. His disappointment is obvious, though. She raises her hands to her mouth, as if to catch a pronunciation. It’s a quiet and evocative moment. And then the camera cuts away from her to a scene a few minutes later.

I’ve been thinking about that particular moment since I first saw “Minari”. The film premiered at the Sundance 2020 Film Festival to rapturous responses, winning the US Dramatic Grand Jury Prize and the US Dramatic Audience Award, and in more than a year since she enjoyed acclaim along the way. The story of a South Korean family making their way in South America is reminiscent of evocative immigrant, family and childhood stories. But I continue to think about that particular boulevard, and the ways it establishes us for pulling rope at work according to the intentions and results of “Minari” and his investigations into family.

The film wins its title from a garden lawn. Early in the film, recognizing his wife’s displacement in Arkansas, Jacob invites his mother-in-law to stay with the family. Soon ja will look after the children, older daughter Anne and young boy David, while Jacob and Monica work in a nearby hatchery. To David’s dismay, Soon-ja is not a typical grandmother. She does not bake cookies, or give a warm hug. She plays cards, and tends to his wounds. And she’s planting. Halfway through the movie, she and the children plant some minary seeds near the nearby bay. The plant predicts growth and health. It’s an easy bit of symbolism: If this plant can grow in the midst of obstacles, surely this family can’t too?

Much of the film is filtered through the perspective of David, the younger child. David is a young boy with a heart defect who requires constant medical attention. Monica worries that the nearest hospitals are miles away. Jacob insists it won’t be a problem. This information arrives early in the film, but Monica’s anxiety never registers as particularly significant. Before the film can really investigate the parental difference in this potential issue, Chung breaks away from the greatest discomfort. In a way this makes sense.

David seems to exist as a kind of avatar for Chung. He’s not entirely the main character, but the sequences in the film depend on his relationship with the initial family quartet, and then the quintet when his grandmother arrives. The family dynamics of the group offer some moments of particular tenderness. The film is mainly South Korean, but parents and children are bilingual. Soon, ja’s english is poor, and the language barrier creates moments of humor and warmth between her and the rest of the family. Late in the film, she comforts her sick grandson with the certainty of what happens when we die who feels too sweet to overlook. And yet, for long periods of time “Minari” feels more impersonal than penetrating.

Chung favors a visual aesthetic that emphasizes naturalism. It makes sense, in some ways. Jacob’s dreams of farming are rooted in an awareness and love of the shining pastoralism. Cinematographer Lachlan Mile shoots the moments in the fields like nature documentaries, finding warmth and beauty in regular yet beautiful landscape moments. But if the film acts as memories of David, “Minari” feels too organized for a film that depicts the mess of good family intentions colliding with one another. Monica asks Jacob to establish what this place is, but the ’80s version of Arkansas feels too smooth overall. This story could be happening anywhere, so it feels unfounded to that particular time and place. There is an airless comfort to the dynamics that make viewing easy even though I sometimes find myself wondering, doesn’t this feel too easy?

And I’ll come back to that cut at first from Han’s face. That avoidance of the harshest moments, sometimes, is a boost. Chung avoids turning this immigrant story into one that focuses on immigrant pain. Therefore, we need only a brief glimpse into their interactions with their white neighbors to understand the dynamics of racism at work. But there is little need for front-load suffering. Instead, in a first encounter with the white church, the camera moves vaguely through the various family members’ interactions with their neighbors. The camera stands back ambiguously, because we can investigate the implications without the need to underline it.

It does feel strange, though, that the same ambiguous tone that makes casual moments of racism so sharp feel out of place when matched against an argument between the couple, or a moment of stillness between mother and her son. The aesthetic silence may be intentional but it also seems to undercut the moments. In the gaps where the story leaves us, “Minari” sometimes feels more intended to get the audience to read ourselves into the gaps than to get the characters to stretch themselves sufficiently to justify it. So the cutaways, when things are about to get challenging, feel more like avoidance than subtext. Every time the movie threatens to find something harder and more interrogative, Chung wanders away.

There is a danger to the way the moments continue, charming in a way, but too vague to pack an emotional wall. Only when Han Ye-Ri returns to the front line does the film feel so complicated. She folds the film to her will in extended glances asking questions that the rest of the film seems determined to avoid. Any ambiguity is forgotten when it hits the screen. As the matriarch of the family, her eyes engulf the screen, creating rich complexities when interacting with any character. This is the kind of performance that harnesses the remote distance of the aesthetics and pulls it into sharp focus. It is fierce work that benefits her scene partners. Every actor becomes better opposite to her. Consider an extended conversation between her and Steven Yeun, who plays Jacob, which is one of the last scenes in the film. The two actors exchange a look of sorrow so knowingly that I was immediately moved more than I anticipated. The look of sadness felt specific to these people, this place, and this time, in a way that the film needed. But then comes a final deus-ex-machina, and with the leap of time as an epilogue, “Minari” deviates us from more difficult complications, once again.

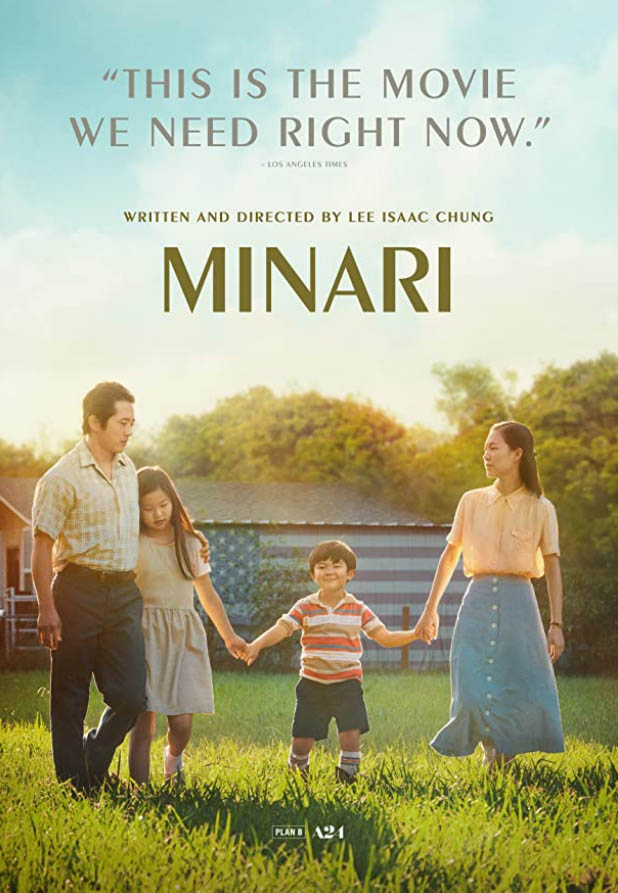

It’s not Chung’s fault that the film has been swept up on the basis that it feels “the film we need right now.” And yet, I can’t even articulate or understand why that calling card is the one used for the movie. The inherent gravity of the American Dream that marks the events of the family’s journey, struggling to grow as the minari plant, may seem hopeful. But it feels impossible not to read the ambiguous reality of the world into Chung’s sanguine aesthetics. That sanguinity, and emotional calm, mean we can see ourselves in the productivity of his family encounters. Under the occasional maze, it’s warm and serious and sweet. But, all too often, that ostensible warmth feels like it’s hiding something hotter, angry, and more restless beneath it.

Minari will be available on VOD release from February 26.