Today’s column addresses the third and last policy choice that I predict Guyana will have to make in this decade. Simply put, the choice is whether to set up by the late 2020s, a National Oil Company, (NOC). As readers will know, at present, international oil companies (IOCs) dominate executive decision-making and control at all critical stages in Guyana’s baby petroleum sector. It is confident that this profile will continue into the coming decade, if it is allowed to run its current course. My prediction is that, on this course, the most likely consequence of the institutional sector is increased variation in the nationality of the IOCs in question. That convinces me it’s just NOC, which can vary this dynamic. The Department of Energy, DoE, which essentially represents the interests of Government, focuses on oversight functions and policy framework guidance.

I have argued for years now to establish an NOC in Guyana. Indeed, this proposal was first raised in connection with the public debates about whether Guyana should build a state-owned oil refinery. I had participated in these previous debates, when Pedro Haas’s feasibility study was presented and discussed on a project commissioned by the Government of Guyana (GoG) three years ago. I had strongly rejected the idea at the time. Readers would also recall that the Haas study found such a refinery too risky, expensive, expensive and uneconomic. Global trends had revealed an increasing surplus of refinery capacity, which made the idea even more unwise.

NOC Profile

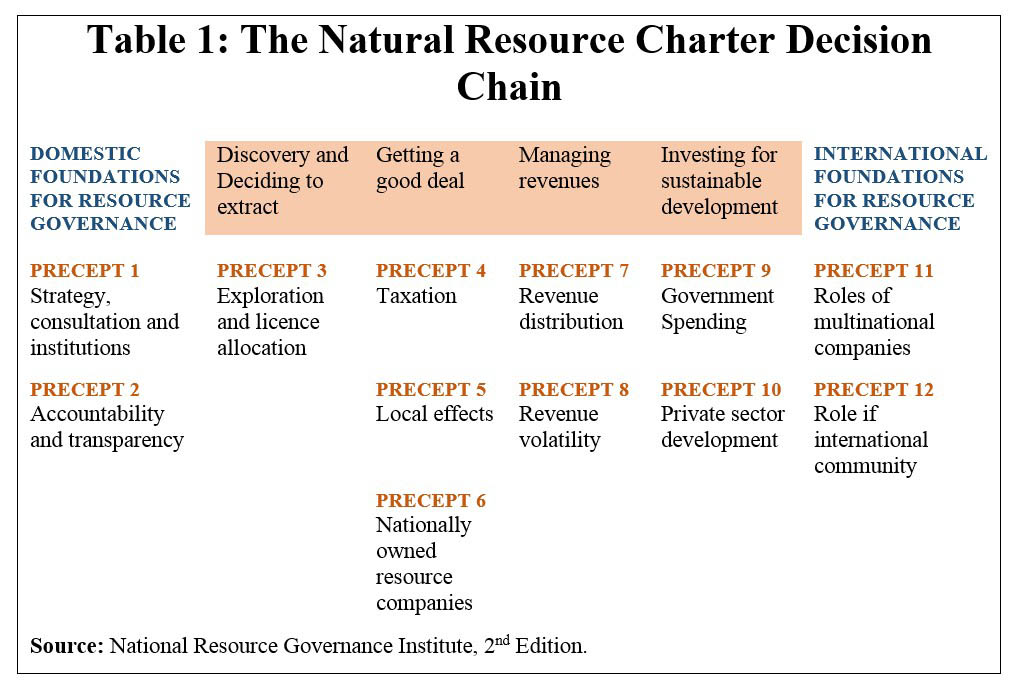

I had advocated NOC in line with that proposed in Precept 6 of the Natural Resources Governance (NRGI) Precepts. Precept 6 of the National Resource Charter, NRC, states: “NOCs should be accountable, with well-defined mandates and an objective of commercial efficiency.” Such a NOC I recommend pursuing a sustainable government on Guyana’s petroleum resources.

NRGI (NOC)

In the NRGI precepts, the NOC is portrayed as a “key component in a strategy to harness the development potential” of Guyana’s world-class oil and gas reserves. As such, it is designed to bring several benefits to Guyana. First, it seeks to capture as much as is economically efficient from the economic rent generated by the petroleum potential. That is, it balances a compromise between captured state benefits and losses by suppressing private investment. It also recognizes that taxes may not hold all the potential economic rents. Second, NOC proposes a way in which technology can be transferred from the operational IOCs (especially in the offshore sector) to local businesses and investors. Third, similar facilitation is expected to take the form of “transfer of efficient business practices” to local commercial entities and entrepreneurs.

From a specific decision-making perspective the nation can also benefit in other ways from NOC. Thus, fourth, the existence of NOC reduces the information asymmetry, which blights the functioning of IOCs in poor countries. It is widely recognized that when there is little information, the best use of resources is most unlikely. Information is therefore key to the efficient use of Guyana’s petroleum resources. NOC facilitates the flow of such information.

The above brings further immeasurable benefit. Fifth, as the metaphor goes, NOC gives Guyana a “seat at the table” of making decisions about the disposal of its natural resources. This means direct influence in executive decision making in the sector. With a seat at the Table, Guyana is in a position to influence the results of the upstream petroleum sector and thus benefit from local involvement policy and building domestic relations in, and between, the oil and gas sector except Guyana petroleum. .

It then follows that NOC should be evaluated from a dynamic perspective. That is, in a context that responds to the evolution of Guyana’s petroleum sector on a global, regional and national level. Such development and its associated activities must be driven by the context and needs of the general environment in which the NOC is located. In this way great care must be taken in assigning to the NOC its respective roles and responsibilities, as well as its guiding governance principles.

A close reading of the above observations suggests that, essentially, an NOC for Guyana should be considered as a tool for its development. In particular, one that seeks to protect Guyana’s national interests in an environment where, at present, the private commercial interests of IOCs are the primary operational drivers. As I will point out later, it costs the State to set up an NOC. These bodies therefore have an opportunity cost and in turn have to justify, or justify, the equivalent of more than the set-up costs. As I will also observe, in trying to achieve this, the State will face risks!

Collection

I consider those issues further next week as well as identify the current size and importance of NOCs in today’s global energy environment.