To Don Drummond

Dem says he was born

with a cauldron,

and not quite opaque

white cover

through whom he visioned

only he knows

At birth I suppose

to be buried

under some special tree.

If we would have known

we could have told them

it was meant to be,

the Angel Trombone Tree.

Taptadaptadaptadada…

Far East

past Wareika

down by Bournemouth

by the sea,

Angel’s Trombone

bellowed sighs

and notes like petals rising

encompasses all that we are.

Not enough notes

to blow back the caul

which falls regularly

and addressing this global vision

hide it from us.

[…]

Lorna Goodison

In 1998, Peepal Tree Press in Leeds, UK, published Wheel and Come Again, An Anthology of Reggae Poetry, selected by Kwame Dawes. By then, the connection between poetry and reggae music was well established. So does the affinity between poets and musicians, as the selections show.

Colin Channer, in the Preface, called it a Caribbean poetry tribute to reggae music, but goes much deeper as Dawes inquires in his Introduction. Caribbean poetry and reggae music connect in a variety of ways, many of which make themselves prominent in the selections, sometimes the poets, and sometimes musicians to whom some poems are dedicated. In addition, the interface between poetry and music has strong historical significance.

The history includes the evolution of reggae itself from the urban grassroots and Jamaican dance halls of the late 1950s. At that time, the productive musical rhythms interacted to provide a new genre in popular music, and more importantly, a local brand. This coincided with the rise of the Jamaican recording industry where competing producers turned out local recordings. A secondary line of creativity was to emerge among the dee-jays who played and promoted the selections. Their poetic lyrics began to take on a life of their own and eventually became recorded as a dub dub. A range of artists such as Big Youth occupied the stage as major performers alongside the singers in the late sixties over to the seventies.

Then, by 1971, Dub Poetry evolved and was first published in the history-breaking, record breaking edition – Savacou 3/4 – at the UWI Mona Campus. Bongo Jerry is a major representative of that group published by Savacou; moreover, he was a pioneer in Rasta reggae poetry. Immediately, leading literary critics Gordon Rohlehr and Mervyn Morris recognized the great value of what was unfolding. At the same time, leading dub poets such as Linton Kwesi Johnson, Alan Mutabaruka, Mikey Smith and Jean Breeze popularized the new form in the UK and the Caribbean. Johnson, Bongo Jerry and Breeze are bloomed in Wheel and Come Again.

By the time this volume came out in 1998, the connection between reggae and Caribbean bargains was well established and already celebrated in the literature. Stewart Brown, Morris and Rohlehr had published Voiceprint, emphasizing the many oral developments in Caribbean poetry that are heavily influenced by speech, oral literature, reggae and dancehall. Not surprisingly, Morris and Brown, both poets, also blossomed in Wheel and Come Again. Significantly, Brown is an Englishman but immersed in the literature and culture of West India. Dawes is a Jamaican literary critic who is also an award-winning poet and short story writer. Interestingly, he also spent many years as a performer in a reggae band. He, therefore, personifies the life of the anthology. He managed to select many different types of poetry from mainstream West Indian poets immersed in the rhythms, reflecting the dance culture, which was dedicated to some of the music legends such as the great Bob Marley, Michael Cooper and Don Drummond.

Some of these ‘literary’ poets have produced immortal verses to suit the type chosen by Dawes. Prominent among them are Edward Baugh, Fred D’Aguiar, Anthony McNeill, Kendel Hippolyte, Olive Senior, Pamela Mordecai, Dennis Scott and Lorna Goodison. Some of them have excellent individual poems that stand as immortal monuments to “reggae poetry”. These include Kamau Brathwaite’s “Stone for Mikey Smith”, McNeill’s “Ode to Brother Joe”, Scott’s “Dreadwalk” and numerous tributes to Don Drummond. The queen of them all is “Valley Prince” Morris, and also included in Dawes anthology are McNeill’s “For the D”, and Goodison’s “For Don Drummond”.

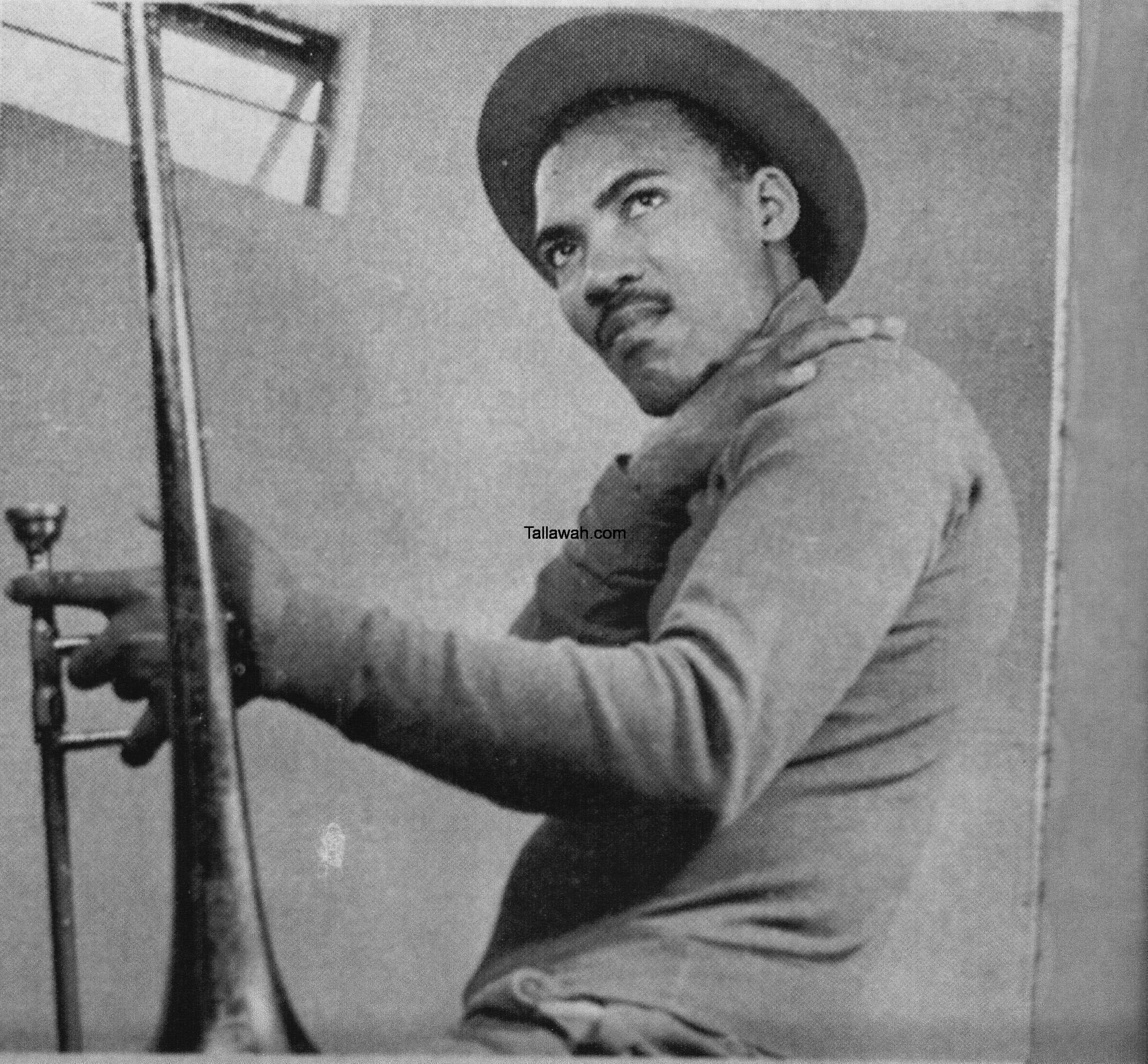

Drummond was one of the marvelous talents of this music. After Bob Marley he is arguably the most respected and is certainly held up as Jamaica’s greatest instrumentalist in popular music. His work as a trombonist spanned the historic walk from ska through rock steadily to reggae. He learned his music at the well-known Alpha Boys School in Kingston, which was already famous on its own as an institution for the less privileged but which became legendary after Drummond’s meteoric rise to the musical scale.

Goodison’s poem celebrates it as supernatural, through its numerous references to the spiritual, the traditional and the human. It is claimed that anyone “born with skin” can see spirits, and Goodison suggests that this gave Drummond his extra gift, extra intelligence, the ability to see what ordinary humans could not do. In fact, his music is considered out of this world.

Similar are the references to the places in which he lived and worked. These areas are found in the “Far East” – the extended boundaries of Kingston East. These are depressed or inner city communities like Wareika and Bournemouth. Wareika is on the East Kingston border with the Wareika Hills and Long Mountain, linked to the urban proletariat and the peasants. Bournemouth is by the sea in Kingston Harbor, still in the east of the city, a popular beach location and nightclub where Drummond performed.

Goodison punishes some of the popular trombonist records, especially “the Far East”. Drummond’s text in that recording was the Far East with reference to China and India. At the time, China was a prominent rising power contrary to the West because of Communism, and world politics was timely where the Far East was concerned. In addition, those distant regions of Asia appealed to the imagination so far away, unknown, mysterious territories, well explored in the notes and sometimes sad tones of Drummond’s music. He had other politically inspired hits related to China such as “Chiang-Kai-Shek”, recorded in the ska era. Chiang-Kai-Shek was the leader of the Chinese Republic which was replaced by Chairman Mao Ze Dong after a civil war in 1949.

What is printed here is only the first part of Goodison’s poem “For Don Drummond”. After this she goes into further detailed references to the musician’s life, especially the tragic side. Tragedy is often associated with genius, as was Drummond.

The title of reggae poetry anthology “wheel and come again” has been taken from reggae in performance. It is the custom of the DJ or Selector to interrupt the flow of a melody with a sudden stop, and turn to the music, often to the satisfaction of the audience. The announcement also states that the poems were “selected” by Dawes. This is a clear reference to the name given to one who actually operates the machine that actually plays the music – it’s a selector.