Transparency International

Last Thursday, Transparency International (TI) published its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2020. Based on surveys conducted by knowledgeable businessmen and country experts on the perceived level of corruption in the public sector, the CPI was compiled using 13 different data sources. of 12 different organizations. For a country to be included, there must be at least three data sources that respond to specific questions relating to:

(a) Bribery;

(b) Diversion of public funds;

(c) The number of cases of officers using public office for private gain without facing consequences;

(d) The ability of governments to contain corruption and enforce effective public sector integrity mechanisms;

(e) Red tape and excessive bureaucratic burden which could increase the opportunities for corruption;

(f) Meritocratic versus nepotistic appointments in the civil service;

(e) The effectiveness of criminal prosecution for corrupt officials;

(h) The adequacy of laws on financial disclosure and the prevention of conflicts of interest for public officials;

(i) Legal protection for whistleblowers, journalists and investigators when reporting cases of bribery and corruption;

(g) State capture by narrow privileged interests; a

(k) Civil society access to information on public affairs.

CPI 2020 results

Most of the 180 countries surveyed have shown little or no progress in nearly a decade to secure improvements in their CPI scores. Two-thirds have scored under 50, with an average score of only 43. TI analysis shows that corruption not only undermines the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic but also contributes to the ongoing crisis of democracy :

The emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic revealed huge cracks in health systems and democratic institutions, underlining that those in power or holding government purse strings often serve their own interests instead of the most open to harm. As the global community transitions from crisis to recovery, counterinsurgency efforts must keep pace to achieve a fair and just recovery.

The countries that continue to score well on a scale of 0 to 100 are: New Zealand (88), Denmark (88), Finland (85), Switzerland (85), Sweden (85), Norway (84 ), the Netherlands (82), Luxembourg (80), Canada (77), the United Kingdom (77) and Australia (77). On the other hand, the countries that scored best are: Somalia (12), South Sudan (12), Syria (14), Yemen (15), Venezuela (15), Equatorial Guinea (16), Libya (17) and North Korea (18).

For the English-speaking Caribbean, Barbados and The Bahamas continue to top the list with scores of 64 and 63, respectively. Guyana received a score of 41 out of 100 and a ranking of 83, a one-point percentage increase over its score in 2019. It has overtaken Trinidad and Tobago which are now at the bottom of the table, as shown in Table I:

TI recommendations

TI has made the following recommendations to assist countries improve their scores and rank on the CPI:

Strengthening supervisory organizations: The COVID-19 response has revealed weaknesses and inadequacies in transparency and oversight arrangements. In this regard, anti-corruption agencies and supervisory bodies must be provided with the funding, resources and level of independence necessary to effectively fulfill their mandates. This is especially true to ensure that resources reach those most in need and are not subject to theft by the corrupt.

Ensuring open and transparent contracting: Many governments have significantly relaxed procurement processes, leading to hasty and transparent procedures that provide ample opportunities for corruption and diversion of public resources. Contracting processes must remain open and transparent to combat tort, identify conflicts of interest and ensure fair prices.

Protect democracy and promote civil space: The COVID-19 crisis worsened democratic decline, with some governments exploiting the pandemic to block parliaments, renounce public accountability mechanisms, and instigate violence against dissent. To protect civic space, civil society groups and the media must have the enabling conditions to hold governments to account.

Publishing relevant data and guaranteeing access: Publishing disaggregated data on spending and distribution of resources is particularly relevant in emergency situations, to ensure fair and equitable policy responses. Governments should also ensure that people receive easy, accessible, timely and meaningful information by guaranteeing their right to access information.

Strengthen supervisory organizations

In Guyana, the anti-corruption and oversight bodies are the Integrity Commission, the State Asset Recovery Agency (SARA), the Public Procurement Commission, the Audit Office, and the Public Accounts Committee (PAC).

Integrity Commission and SARA

Successive administrations have failed to fulfill their obligations to deal sympathetically with corruption, paying lip service to the two international conventions for which Guyana is a signatory – the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption. The Integrity Commission, set up by legislation 24 years ago as a result of the first, has a brutal track record in its operation and is currently starving resources to enable it to fulfill its mandate effectively. SARA also appeared to be non-functional, and its effectiveness left much to be desired. It has since been dismantled by the new government.

Public Procurement Commission

The Public Procurement Commission is responsible for ensuring the procurement of goods and services and the execution of works in a ‘fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective manner’. Compliance with the Procurement Act is required to be monitored. However, after 15 years since the Constitution was amended to provide for the establishment of the Commission, the Commission’s five members were only appointed until 2016. In addition, since October 2019, the Commission has been without the services of three of its five members because their tenure of appointment ended, with no replacement. The tenure of office of the other two members ended in October 2020.

The Procurement Act regulates the procurement of goods / services and the execution of works to promote competition among suppliers and contractors as well as fairness and transparency in the procurement process. However, the Auditor General’s successor reports have highlighted significant breaches of the Act such as failure to adhere to the tender process; splitting contracts; and lack of effective monitoring and supervision, resulting in short distribution of goods / services and overpayments to contractors. Why are these cuts allowed to happen year after year without evidence of any sanctions on defective government officials and suppliers / contractors?

Audit Office

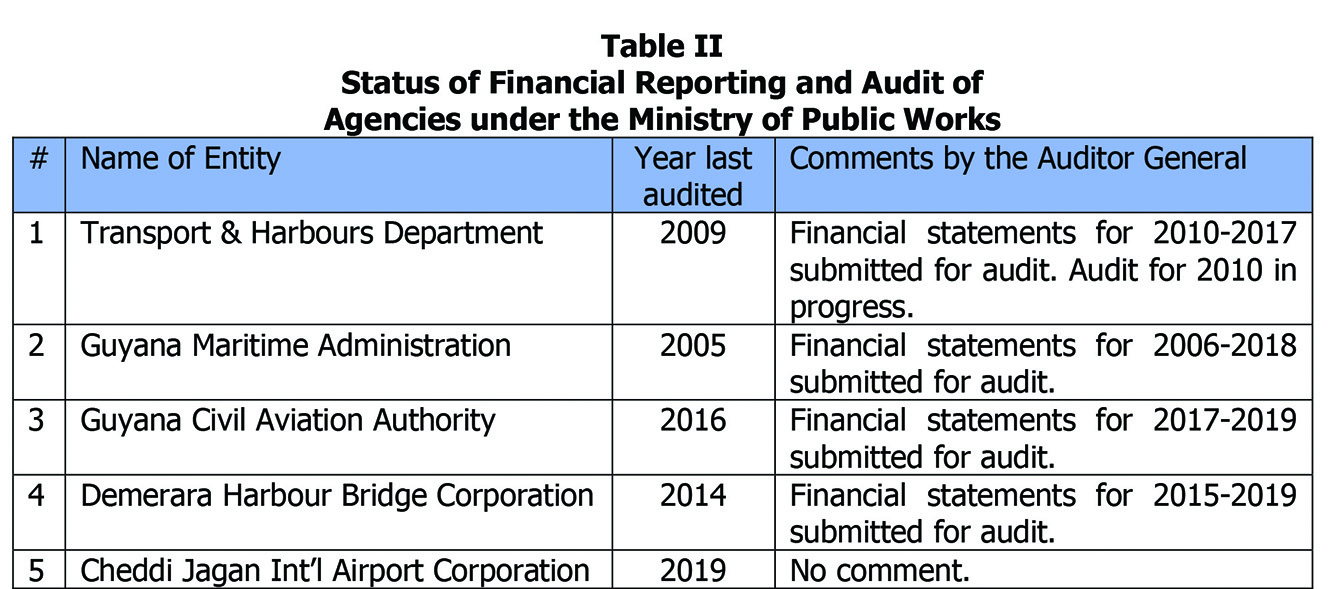

Although the Audit Office has been timely in producing audited public accounts, the quality and comprehensiveness of the results has left much to be desired. Apart from that, the focus has been primarily on central government activities, considering that the public accounts also include local government bodies and all entities that vest interest management in the State. Many of these entities, which hold significant amounts of backlogged accounts in the Audit Office, may be subject to greater scrutiny awaiting audit. For example, in his 2019 report, the Auditor General reported on the status of the five entities under the Ministry of Public Works that have made news in relation to the purchase of gifts to government officials, in accordance with Table II.

It would be in the public interest if the Auditor General published the list of entities that his office is required to audit and the status of these audits, including the accounts held by the Audit Office which waiting to be examined, and for how long.

An annoying aspect of the Audit Office’s work is that the Auditor General is being asked to carry out ‘forensic’ audits of areas on which he had already certified and articulated. Two examples will suffice – fees paid for legal services at the Ministry of Legal Affairs; and the overhead expenditure is overrun on the East Bank Demerara. He will also be asked to undertake a similar assignment at Georgetown City Council when his office still has years of Council backlogged accounts to audit.

The Auditor General walks a thin line and has to be careful when asked to undertake politically motivated assignments, and not jump at any request. One recalls the request by Cabinet in early 2016 for its office to conduct a transaction audit of National Industrial and Commercial Investments Ltd. Five years on, the Auditor General has yet to honor this request. The WAO needs to focus on the significant amount of backlogged accounts it holds, rather than playing to the gallery and pandering to the wishes of the politicians.

Public Accounts Committee

The LLP is responsible for examining the accounts which show the appropriation of the sums provided by the Assembly to meet public expenditure and what other accounts laid before the Assembly as the Assembly may refer to the Committee together with the Auditor General’s report on it ‘. Its last report was in respect of 2012-2014 and was published in July 2017, some five years later in respect of 2012. The LLP is currently auditing the public accounts for the year 2016, and their results will be reflected in a consolidated report for 2015-2016.

The other accounts required to be laid in the Assembly are the accounts of public corporations and other entities in which interest management vested in the State as well as those of other statutory bodies. Section 80 of the Financial Management and Accountability Act requires these bodies to submit annual reports (including their audited accounts) within four months at the end of the financial year to the Ministers concerned; and for these Ministers to submit to the Assembly within two months of their receipt. However, more often than not these requirements have not been complied with. In addition, while LLPs require greater scrutiny of the accounts of many of these bodies, they are not referred to the Committee for such scrutiny. It is hoped that the current LLP will insist on complying with the above requirement and begin to audit these accounts.

Throughout the whole post-Independence period, the lack of timeliness of its audit and reporting has adversely affected the effectiveness of the CAP’s work. This has resulted in the examination of backlogged accounts as well as the Auditor General’s findings and recommendations repeating themselves in successive reports. Our analysis has shown that it took an average of three and a half years after the Auditor General’s report for the years 1992-2014 was published, for the LLP to complete its audit and report back to the Assembly. Does this not explain why the Auditor General’s findings continue to repeat year on year?

Unless the LLP can facilitate its audit and reporting of public accounts, its work will continue to be an academic exercise, and the Auditor General’s findings will continue to repeat themselves year on year. A fundamental principle of public financial management is the timeliness not only of financial reporting and audit but also of legislative scrutiny of outcomes and of taking steps to remedy the deficiencies highlighted. Indeed, delayed public liability is denied!

To be continued –